it's the opening night for Frieze, October 13, 2010, the London art fair. It's a madhouse. Thousands of art lovers, collectors, and the glamour crowd are squeezed into the famous tent in Regent's Park. This year, more than ever, it's bursting at the seams.

There's a particularly strong contingent of young people this year: people of a similar age to Jin Shan, the only Chinese artist to be represented in Frieze's prestigious Frame section of the fair. Jin Shan’s work has some prominence here. His gallery, Platform China, in Beijing, has been awarded a spot close to the start of the section. The work, then, being close to an area left open to mark the transition into the framed section and to allow visitors to congregate, occupies a prominent position, but is simultaneously obscured (almost) by the brilliant glaze of overhead neon and the general sparkle of opening-night fervour. For this reason alone, visitors would have been forgiven for overlooking, Jin Shan's video installation, One Mans Island, or for catching, at best, but a passing glimpse of its stark, dark content. Its darkness references the underbelly of one man's solitary existence and stood, in this moment here in London, in dramatic contrast to the general aura of the evening-not dissimilar to dropping by London's 100 Club (on Oxford Street) on a Tuesday night in May 1976 to glimpse an anguished Johnny Rotten in mid-performance, hunched over a microphone into which he would have been squawking, unintelligibly to most, offensively to almost all, and entirely out of synch with the broad commercial environs that continue to surround the club on street level. At that time in Oxford Street back in 1976, fascinated angry teenagers aside, the majority of Londoners, had they braved the punks crowding the entrance and descended into the bowels of the club, would have winced in surprise; more shock and horror. Meanwhile, passersby inevitably continued on their way that bit faster; that bit more inured to the perceived excesses of youth. That was the overriding impression I had watching the crowds milling around this section of Frieze: a second, and revealing reason, that the work was effectively glossed over. It didn't take Punk co prove how unusual, confrontational, anarchic, or nihilistic human behaviour tends to have that effect, and although Jin Shan is no latter-day punk himself, the presence of One Man's Island at Frieze, in spite of playing to an audience of the enlightened, who largely believe themselves unshockable, had exactly the Johnny Rotten effect.

How different the impact through November and December 2010, back in Beijing, where One Man's Island was presented to its fullest dramatic effect in the ample second-floor exhibition hall of Platform China's B Space. There, quite simply, it proclaimed itself the most arresting work by this artist to date but also to have been seen in Beijing for some time. To say that words dej an accurate description of the work is a tribute to the potential of the artwork, by its nature visual, both in terms of the artist's choice of medium (art) and the audience experience thereof. Too many works these days make for better literary reading than optical viewing. One Man's Island is an exception.

The nihilism habitually associated with Punk offers a first reference point for the framework within which Jin Shan's adult experience operates and of which One Man's Island is the inevitable conclusion. The appearance of Punk terrified a society unused to teenage rebellion: not in that form, at least, for it went far beyond the decline in social mores insinuated by 1950s rock 'n' roll or 1960s free love. Punk was a manifestation of despair and hopelessness honed to anger at a society that denied youth a space in which to take full responsibility for their own emotional state and decision-making. This wasn't the generation that wanted to change the world, but its sibling-successor that watched those dreams of change, hope, and opportunity evaporate under the weight of economic decline and a retroactive resurgence of conservatism and wondered where the fuck that left them. Jin Shan was born in 1976, and he was too young to be overly affected by the events of 1989 (June 4) but, come the mid 1990s, as he entered his twenties, he was a perfect age to be infected with the malaise that circles the single-child generations, for whom Joneliness, isolation, alienation, and apparent opportunity and plenty are contradictions that have yet to be reconciled, not to mention the death of dreams of democracy, of freedom of speech that remain ghosts in the present, lingering in the caverns between the 'peaceful" spread of new economic order and the cloistered violence of responses to that order by those who remain disenfranchised. Ironically, it is exactly Jin Shan's generation of contemporary youth that has the tools to be most aware of the social fracture, it being most adept at circling firewalls and delving into the vast well of information at the disposal of the cyber community, where outrage and calls to arms abound.

One can only surmise that it is the fact of the "great" proletarian revolution in China, which Mao both incited and sanctioned in August 1966, that has thus far all but denied any spirit of rebellious, anarchic, or "punk" youth in China that, and the size of the country with its local cultural disparity between states that are the size of European countries. Yet August 1966 saw millions of young people descend on Beijing's Tian'anmen Square to salute the Chairman. His act of approval united them in an almighty movement and set them on a path at least as destructive as any Punk rock gig, and on a scale of which Punk's anarchists could but dream. As the trauma was compounded in 1989, the Chinese people have still not recovered sufficiently for a further boot of teenage angst to burst forth and challenge authority. It might never happen, not in the way exemplified by the very Western-styled Punk scene. And yet Jin Shan's recent work, this solitary without hope, without reason, without visible structure or community, without past, and following all visual signifiers and suggestions, without any meaningful future, which is the very embodiment of the 1977 Punk anthem these qualities are desirable in any capacity at all:

Don't forgot howl got to this place. It was dark around when I woke up and nothing could be seen. I stretched out my hand, separated my five fingers and finally I could see a half moon. The moonlight penetrated through my fingers and poured onto my face. I felt cool; the wind was up. I stood up and flipped off the mud on my bottom. The light went on and there was a lonely chair in the corner near the window, covered with dust. I looked down, but there was not a single footprint on the dusty floor. I became more confused. How did I get here? How long had I been here?5

This is the realm into which Jin Shan plunges his audience. Unsuccessfully, perhaps, in a setting such as Frieze, where an intimate encounter with any video work was inevitably neutralized by the lighting levels, but a paramount success in a blackened room.

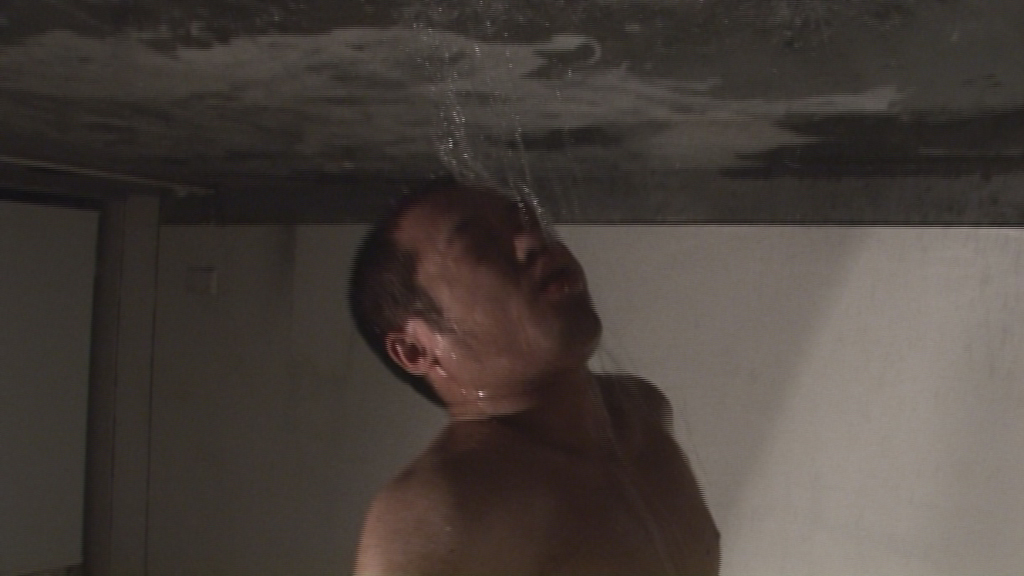

One Man's Island is a video work that, as of the end of 2010, comprises fifty individual video sequences of varying length that have each been filmed within the artist's studio or in an environment selected by the artist and that for the most part feature the artist, Jin Shan, engaged in an action or activity that can only be described as nervously mindless. This quality of nervousness seeps through the images and infects the audience's experience of the artist's island demesne, especially where the artist-auteur appears superficially-in the majority of the filmed sequences--to maintain a level of controlled calm that is at moments chilling, at others profoundly disturbing. In the artist's words, One Man's Island is "a growing diary-like video project, expressing and recording personalized physical and mental experience through video, and thereby re-observing the possibility of confrontation, dialogue, and mixing of daily life and art creation” 6

Such explanation sounds rational enough, but that is far from the effect that this work achieves. Jin Shan's island is absolutely solitary: the "one man" in the title does not pretend to claim a distinctive individual vision, which no other man could have dreamed up, but an island upon which one solitary being exists, ever uncertain of the nature of his own existence.

I couldn't see myself. I was transparent. I didn't exist. I bent my fingers and held something with two of them. I raised my head and arms, and my ass moved out of the bench lightly. It seemed that I was shouting someone's name out, or I was trying to recollect an unfamiliar melody, or trying to put the letters in order. I moved my shoulders from light imagination over one hundred years ago.

One Man's Island is perhaps best described as the physical application of "craziness" born of "pure imagination." This is Jin Shan's personal interpretation of a vision of experience, not a prophetic incantation of universal reality, though like the best personal visions it plays out in universal terms. This is also what ought to make this work enduring: Jin Shan's impulses draw an unflinching line from the performative actions of Joseph Beuys to Jonathan Meese via Martin Kippenberger. What makes the breadth of emotions and actions brought to One Man's Island so astonishing is the intensely introspective character of the artist, who quite in contrast to the person that takes centre stage in this work is apparently happier to blend into the background in any public arena he can be persuaded to enter.

I first encountered Jin Shan in the exhibition Shouting Truth, with a video work titled Hanging Flesh (2006). He was the sole perpetrator of the action, but where the filmed sequence was replayed upside down, it took the viewer some time to match the face to the artist. Especially where the artist, despite appearing to be the right way up on the monitor, was, in fact, hanging by his ankles, which caused the blood to darken his face and to draw an apoplectic expression across his distorted features. The effect was captivating. Here, I assumed, was an exciting young artist in the demonstrative and non-prescriptive tradition of China's pioneering performance artist Zhang Huan. This assumption could not have been further from the case. Jin Shan's work is exciting, no doubt, but the artist is the embodiment of painful shyness enveloped in a further layer of reticence towards casual communication. That, it has to be said, is entirely refreshing in a period where each artist is both the best articulator and verbal analyst of his or her own work, and where the artist's words frequently occlude the work itself. It was something of a surprise then to learn that One Man's Island began, not from the spoken word, but from a series of writings: of diary-like jottings. More so, where Jin Shan had collected and collated these writings into an order--not of narrative as much as of experience or inception-and consented to their publication as an independent book of some 300-odd pages (including Images and translation). Here, words pour out in a stream of consciousness that swerves between compulsive Tourettes-style expletive and adolescent naughtiness, poetic despair in the manner of Rimbaud (to whose words I kept being drawn in the course of viewing One Man's Island) and raw terror at life and death, between pure imagining and all that waylays the sensitive, individualistic, non-conformist (in mind if not in action) contemporary individual. For such individuals -for an artist like Jin Shan- the meat of daily life is not enough to content his creative impulse. There's a further realm of questioning, of experience or insight, of isolation and of fear, always the fear of all that is unknown, which demands engagement. As one comment in his writing reveals: "Most of the time, I thought I knew everything, and was as omnipotent as every other person. I could describe the shapes, sizes, colours, materials, and positions of things even if they didn't have names, but the ironic thing was that I couldn't be that proud-I was unable to describe the things I saw, never.

This questioning that drives the writing is never fully resolved ~What kind of person did I want to be? I asked myself. I conjured up several persons and talked to them. . . . What would I want to be? A healthy man, a kind man, a man who lived comfortably, a man who could talk with birds." But then we would be disappointed if it did. A neat conclusion to the angst that abounds in Jin Shan's work would turn the work on its head, making it a childish, pathetic grappling for attention instead of the profoundly intelligent gesture it represents.

The process of conceiving and creating the work becomes a map of the ways in which the day's routine, Jin Shan's daily life, unfolds. The book contains a passage that is both evocative of One Man's Island and descriptive of the action the audience can expect to see:

My day (another day)

Drink a glass of water (piss); put the cup into the box; (cover the box on the cup); scoop up some rice with a bowl; (pour the rice into a bowl); put left hand into right hand; (put right hand under left hand); lean a stick against the cabinet; (push the cabinet down on a stick); draw the curtain in front of a window; (cut the window into smaller size that equals the width of the undrawn curtain); put on a coat; (take of the coat); take a puff on a cigarette; (finish a cigarette as one go); turn over the cover of a book; (turn over all the other pages except the cover); peel an apple with a knife; ; (scrape the apple on the knife); nail a screw into a wooden board; (spin the board with the screw); circle and stroll in the room; (feel the room is circling with me at the same speed); carelessly knock over a bottle of ink on the table; (turn over the table and cover its surface on the mouth of the ink bottle); write down a name on a piece of paper; (move the paper on the pen to write the name); listen to the music for one minute; (think about music 'or one minute); draw a picture; (throw the painting frame onto a stack of paint boxes); turn on a light at night; (turn off the light and go to sleep).

These are precisely the actions Jin Shan carries out in the work. Thus, in the filmed sequences, the type of description reproduced above functions as a stage direction, which the artist-auteur duly follows. Indeed, each of the separate scenes and the actions that take place in them is preceded by a title frame not dissimilar to those once employed in silent movies. Similar to the list above, the words in these frames are meticulous to a fault in heralding the act the artist is about to perform: ". . . draw on this paper, or turn it into a coaster, or roll it up, make it into a trumpet and cover it on my head” Or make a self-portrait using ''a cone set up by three iron sticks, and on top of the Cone, a limp plastic disc." Such lists of instructions are not uncommon paraphernalia attached to performance art events --certainly similar to those listed by Zhang Huan ahead of a mass performance work. Yet, in the normal run of events, they are purely practical, an easy means of communicating with the participants the steps they are required to take, of directing a group action. The actions and gestures featured in One Man's Island differ in that they are entirely private performances, actions carried out far from any audience presence. One senses that it is this distance from a close proximity to a human reality that allows Jin Shan the freedom to act as he desires and with the required degree of intensity. At least, that distance is necessary if the attention given to the details within each scene and action are to achieve the requisite sense of urgency that Jin Shan deems necessary for conveying their import to the audience. That importance, Jin Shan seems to suggest, lies in their being the artist's only means of keeping the abyss at bay, and shutting out the darkness of isolation and the utter meaninglessness of one man's existence. It is here where phrases like ". . . something was evaporating fast from me. . . . I wanted to tell you there was nothing beautiful in life; to live was to suffer" most closely convey the mental Strife that drove Rimbaud's. A Season in Hell: "Does this farce have no end? My innocence is enough to make me cry. Life is the farce we all must play.

There is something utterly Punk about the state of mind and attitude evidenced in Jin Shan's on-screen actions, as much as the writing itself: "He crouched in a stinking bog for three days and nights and wouldn't come out. Merciful people, serious people, people in hats, crying people, md murmuring people, no one could persuade him. He rolled the stinking mud into balls and threw them at the people, he laughed at then and called them arseholes. . . .15 The parallels with Rimbaud a punk in his time, to be sure are endless and, in the absence of Jin Shan's work itself, evocative of its essential mood:

I belong to ancient race: my ancestors were Norsemen: they slashed their own bodies, drank their own blood. . . . I'll slash my body all over, l'll tattoo myself, I want to be as ugly as a Mongol: you'll see, I’ll scream in the streets. I want to get really mad with anger. Don't show me jewels; l'll get down on all fours and writhe on the carpet. I want my wealth stained all over with blood. I would never do any work. . . .

Several times, at night, his demon seized me, and we rolled about wrestling! . . . Sometimes at night when he's drunk he hangs around street corners or behind doors, to scare me to death. . . . I'll get my throat cut for sure; won't that be disgusting.

Across more than a century and several continents, two similarly natural-born artists collide in a hypothetical Venn diagram, which ultimately represents the transcendence of cultural frameworks and historic moments: the kind of universal humanity of which Western history so readily speaks. Ultimately, the attitude that escapes Jin Shan in One Man's Island feels vindicated: by the time You've viewed the fiftieth sequence you almost understand how the need to be excluded, to be exiled even, seems a route of less suffering than the road to conformity. At least, here on this island, Jin Shan holds true to his integrity. "Since I dislike travelling, this island fits me well”

This level of disaffection is of course not unknown or invisible in China. From post-June 4 through the 1990s, it was evident in the art world, and is most prevalent today within the burgeoning (underground) music scene, although prior to 2000 or so the lack of performance space largely kept the musicians out of the running. Even so, the level of anxiety that underpins the aura of nihilism in this extraordinary work is shocking. More so when you consider the potential extent of the pain and trauma at work beneath the surface of everyday humanity in China, both of which are effectively repressed by the majority, which lacks the courage -more than the tools per se- to vent their emotions via creative expression as Jin Shan does here. At the same time, we have to remember that even within the realm of cutting edge art, Jin Shan is an almost entirely isolated example of such intensely personal and unaffected human emotion, be that an autistic brilliance, a mentally incapacitated complexity, or a deliberately childish inanity. Here, it is important, perhaps, to stress that Jin Shan is self-taught; this is significant in a country where the art world is almost exclusively composed of art school graduates, most of whom were also born into privileged families. "what I can promise,'' Jin Shan assures us, "is the thing l'm presently doing. Why I am doing it?. I can't remember. Where will it lead?

In One Man's Island, it's hard to tell initially, but once the entire collection of videos has been viewed, the conclusion is indisputable: genius.