Using text as motif in paintings is not rare. Such retrieval and conversion has been common practice in the history of art since ancient times. Most artists see it often as a purposeful choice or just as a way of accomplishing a painting. For Liu Gangshun, however, gathering texts and selecting image and motif from them is inherently a part of his painting language, and even his everyday life.

What Liu pays attention to and depicts are mostly not physical objects in reality, but mainly comes from certain image or text or his reading experience at a certain moment. So this series of paintings always exhibits “a painting within a painting” characteristics, and we can even say almost all his paintings are “meta-painting” practice. Of course, instead of being dogmatic and rigid, they involve multiple self-reflexive mechanisms Liu incorporated, visible or invisible.

“Fable of the Bees”

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, Liu, like most other young artists then, was obsessed with avant-garde art and vanguard literature developing in European and American countries. In 1995, he opened “Posthuman Bookstore”, an independent bookstore in Huangshi, Central China’s Hubei province. For a period that followed, he got exposure to different radical thoughts and experimental texts. Fanaticism, anger, rebellion, desperation — each once overwhelmed him. He fantasized about communism, longed for liberalism in a utopia, and even became crazy about anarchism… That state continued until 2002 when Liu, nearly 40, closed the bookstore, went to Beijing alone, and devoted himself to painting. While starting to reflect on the past passion in his prime, he made a bold decision: detach past experience and emotions completely from his body and mind and take them as an object or matter that can be analyzed and understood.

The painting journey of Liu restarted in 2004 through A Year Starting from Johns, which also marked the beginning of his life and career in Beijing. It is a series of works where Liu imitated a set of texts from The Seasons Jasper Johns created and displayed at the Venice Biennale in 1985. The American painter appeared in his later paintings many times. Johns bears special significance to Liu who saw the metaphor for life in the former’s paintings. And more important are the “materialization” and “dehumanization” features contained in those paintings. “… in this picture by Jasper Johns, one felt the end of illusion. No more manipulation of paint as a medium of transformation … There is, in all this work, not simply an ignoring of human subject matter, as in much abstract art, but an implication of absence, and … of human absence from a man-made environment. In the end, … Only objects are left—man-made signs which, in the absence of men, have become objects,” art historian Leo Steinberg sharply pointed out, believing it indicates the arduous process for a new art creation to get accepted, and at the same time reminds us that the indifference and desolation is a prelude to a new age.[1 Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, Translated by Shen Yubing, Liu Fan and Gu Guangshu, Nanjing: Jiangsu Fine Arts Publishing House, 2011, p.27-32.]1 All happened to strike a chord with Liu’s mood and choice at that time. True, it can be considered a kind of experiment with painting itself, but for Liu, I would rather call it introspection about his life. From then on, the Fluxus artists and Bob Dylan who once excited him emotionally became text motifs he rationally analyzed and depicted.

As art historian Svetlana Alpers put it, each artist has his/her own museum. It may be a real museum or gallery, in his/her studio, on the bookshelf, or even in his/her head.[2 See Svetlana Alpers, The Vexations of Art: Velazquez and Others. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007, p.1.]2 The same is true for Liu. His museum is in his studio, on the bookshelf, and in his head. The painting albums, novels, poems and theoretical writings previously keeping him company served as the chief way he collected source materials of his paintings. “Collecting” as a way is one of the procedures for painting, and also part of his painting language. One can image an art history of the twentieth century dynamically unfolding in his studio or at his exhibition. Interweaving and bursting freely are classics from artists like Kazimir Malevich, Martin Kippenberger, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Joseph Beuys, Josef Albers, On Kawara, Michael Heizer, Richard Serra, Cindy Sherman, Francis Bacon, Roy Fox Lichtenstein, Yves Klein, and Sigmar Polke.

Besides being a way of painting, “collection” as the original form of “meta-painting” also is a kind of knowledge mechanism. As early as in the seventeenth century, such form of “a painting within a painting” already prevailed in Flanders. The most classic examples are a series of “Cabinet of Curiosity” paintings co-created by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, as well as “gallery paintings” by David the Younger Teniers. For instance, Allegory of Sight (1617) by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder is a typical “painting within a painting”, or “meta-painting”.[3 Victor I. Stoichita, The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting, Translated by Anne-Marie Glasheen, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, p.83.]3 Beyond that, art historian Victor I. Stoichita spotted the meaning of “collecting” or “gathering” is inherently conveyed in one of the painting’s motifs, “flower”. On the “bouquet” meaning “collection”, is a bee, a metaphor for “alchemy”, and the painter acts as “flower farmer”. Both the form and metaphor contained in the painting echoed the encyclopedic “all-knowing” movement of the seventeenth century; as a kind of productive practice, they also resonated with what contemporary thinker Bernard Mandeville described about flowers and bees and their productive action in The Fable of The Bees. Flying across flowers, a bee collects nectar and carries it to the honeycomb. As pollen from a flower sticks to its rubbed legs, it will be carried to the next flower the bee flies toward. It is precisely through the bizarre encounter and initiative production that a new combination emerges, together with numerous common new forms.[4 Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri, Commonwealth, Translated by Wang Xingkun, Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2016, p.145-47.]

Just like a bee, Liu is also a collector, producer and “alchemy worker” of images (knowledge). This, of course, represents how knowledge is generally produced and images communicated in the Internet era. But in his eyes, there exists not only a museum or gallery, but also a library. Apart from the classics of the aforesaid artists, Liu also incorporated words from the texts by writers — such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, Cummings, Guy Debord, Samuel Beckett, Raymond Carver, Thomas Mann, Raymond Queneau, Sartre, and Henry Miller — into the motifs of his works. His practice is reminiscent of that by art historian Aby Warburg and Jewish thinker Walter Benjamin 100 years ago. In the 1920s, Warburg built a library meant to break the existing classification system for disciplines, and embarked on a matching project, the Mnemosyne Atlas. The unfinished project can be interpreted as the visual equivalent to the Arcades Project collage by contemporary thinker Benjamin. Similar to Warburg, Benjamin liked buying and collecting books and looked forward to owning a library. It is said that he had originally planned to accomplish a work entirely composed of quotations, which, unfortunately, was not realized before his death. Though not directly influenced and inspired by the two, Liu resembled them in approach (including opening the bookstore). The difference is the “quotation (image) assembly” and “garble” by Liu do not resort to certain narration, nor relate to certain existing system. Instead, what really matter for him are uncertain perception and concept conveyed and unleashed by those words. The first and foremost is the complex and changeable word-image relationship.

Words and Images

As with “meta-painting”, the relationship between words and images is a classic topic in the art history, or even a part of “meta-painting”. This article is not intended to trace its long and complicated history, and Liu’s practice has no direct bearing on it. In comparison, he combines word and image just right, albeit in a seemingly “simpler and ruder” way.

Word-image interrelation is among the most common languages in Liu’s paintings. In Portrait of Kippenberger (2008), he focused on one painting representative of works by Kippenberger, Waiter of… (1991), using the plainest realism technique. The curved floor lamp that repeatedly appeared in paintings and installations by Kippenberger gave Liu a glimpse into his tragic life. Nonetheless, what Liu presents is not the scene of the exhibition but comes from an album of paintings. On his own work, Liu marked letters “Kippenberger” in bold, producing a word-image relation. The relation implies the bending floor lamp represents the image of Kippenberger as he understands, and reminds the viewers that the work is only a text, or even the cover of an album of paintings by Kippenberger. Another work This Is Not Marlboro (2006) adopts a similar approach. The main part of the painting is a masterpiece created by De Stijl painter Theo van Doesburg, Composition XI (1918). Worth noting is Liu changed its color entirely to black when borrowing it as a motif. At first glance, Liu’s work looks more like Malevich’s “Black Square”. At the bottom of the painting is a partial view of two Marlboro cigarette cases side by side, with “Marlboro” replaced by “Malevich”.

“What the Cross represented to the early Christians, the square represents to us.” Doesburg wrote in 1922 in a letter. “The square will conquer the Cross.” he said in another letter the same year. Besides, many De Stijl members frequently mentioned “spirituality” in their writing.[5 Paul Overy, De Stijl, Translated by Li Bowen and Proofread by Xu Xinwei, Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2020, p.33.]5 As the symbol of “conciliarism”, “Black Square” is perceived by Malevich as a supernatural form, and thus endowed with some mysterious and religious aura. “Marlboro”, without doubt, refers to the American consumerism. Here the meaning is “Malevich” has become a symbol for consumption like “Marlboro”. In turn, as a symbol of consumption ideology, “Marlboro” industry is exactly the same as religion. So, for one thing, mysterious “Black Square” becomes the consumption symbol, to all appearances; for another, it reveals the religious side of pop. The so-called “fetishism” is also a kind of religion. But, when seen from another perspective, it cannot be ignored that De Stijl is essentially connected to the formalism theory closely. Formalism seemingly sets form against object, but in fact, the precondition for formalism is “materialization” and “dehumanization”[6 Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, p. 103.]6 of a work. In this regard, it is actually not different from pop. Obviously, Liu is interested not in the part as object, but in the spirituality and willpower behind the objective form and object. The image of Malevich repeatedly appeared in his paintings. The background of Russia (2007), for example, is a “black square”, with letters “RUSSIA!” in white bold written in the middle of the painting. For artists, “black square” symbolizes the spirit of Russia. But the point worth pondering is he just wrote “RUSSIA!” in English, not Chinese, not Russian. Therefore, although the words and background image seem consistent, some kind of implied split exists between them.

The word-image relationship is not confined to the symbolic level. Sometimes, color and form perception is also a part of a painting. “Poet” with gray background, “Simple” with blue background, “Wood and Charcoal” with yellow background, “Art Is Useless, Go Back Home” with red background, and “Life Is Dangerous” with white background, to name a few. There seems no connection between these colors and the text, but the fact is our perception of background colors directly leads us to the text. “Never Work” is a famous slogan proposed by Guy Debord. The avant-garde movement (Letterist International and Situationist International) launched by him between 1952 and 1972 came as a huge shock to the entire western world. Debord did never worked, even distaining to receive formal education by going to college. He drank, wandered around the streets, wrote, and made movies, and even used slowdowns and shutdowns to rebel against the degenerate society. His book The Society of the Spectacle published in 1967 sowed the idea seeds[7 Fei Dawei, Never Work, http://art.china.cn/voice/2013-07/25/content_6151174.htm (in Chinese).]7 of the May 1968. The “Never Work” manifesto came from it. In the Never Work! (2012) by Liu, he did not add image processing on purpose as the text in it represents image. But the shape and structure of his painting, including the typeface, looked like the doorplate of traditional labor and public institutions. So hidden behind the ingenious integration of word and image in form is split and conflict at one extreme. His new painting Caution! (2019) features a blue background, with two Chinese characters “Dang Xin!” meaning caution written in the center in bold and light gray. He intentionally retained grids drawn before painting to control font and size, especially lines varying in length and their strokes — indicating some kind of danger and uncertainty. Here, word and image correspond, or we can say word itself is the image or a part of it.

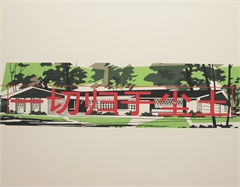

Not all paintings contain text or concept, and some only have images that artists claim actually derive from specific text. Liu finished World (2019) using a part of the land art work City: Complex One (picture) by American artist Michael Heizer. Liu reinforced the sense of composition in the picture, especially the hard-edge processing technique and orderly segmentation and sense of detachment. In addition to the contrast with the remote mountains, violence and danger lurk. Heizer once called “urgency, suffering, drama, and hazard” the “requisite conditions for making art”, so “My work, if it's good, it's gotta be about risk,” he said. “If it isn't, it's got no flavor.”[8 http://www.qdaily.com/articles/31687.html?source=feed.]8 What Liu presents is not so much a re-portrait of this picture as a visual interpretation of what Heizer said. In the work by Heizer, it’s not difficult to gain insights into the landform of the desert in Nevada, United States, where the work is based, and the strength unleashed by it. Dissociated by Liu, the desert landscape is conceptualized into geometric composition, with white lines being a metaphor for speed, highlighting the juxtaposed triangle installation in the foreground, the strength and danger conveyed from its shadow, and its universality. Another work that applies the similar approach is World Factory (2015) derived from non-fictional work by Chinese-American writer Leslie T. Chang, Factory Girls. She spent years tracking and interviewing girls who worked and lived in factories of Dongguan about their living status and fortune. A symbol for “world factory”, the Chinese city created a legend and became a metaphor for globalization. However, Liu painted it as an abandoned factory, just like a desolate island. As Liu created the painting, the legend of “world factory” was already a thing of the past. Then where did those factory girls who worked there in the prime of their life go? And where are they now? Maybe this reflects Liu’s true intention.

If World Factory offers an exterior view of a desolate island, then another work 1984 completed the same year seems to be a part of its interior view — a corner of a bathroom, with a urinal on the right-hand side and a waterless hand washing sink on the left-hand side. The confined space is reminiscent of the depressing and suffocating atmosphere created in anti-utopian novel 1984 by George Orwell. The oblique look-down perspective used in the painting is an indication that it may come from the look of the “Big Brother”. As a matter of fact, “84” is “48” in reverse, so Liu is looking at what happens in 1984, 34 years after 1948[9 Li Ling, Birds Sing: Twentieth Century in Retrospect (in Chinese), Beijing: Peking University Press, 2014, p.34, 43.]9. Today, whether for socialism or capitalism, ubiquitous power and surveillance Orwell imagined and predicted in his book has become the norm and habit in our life. When the epidemic broke out, mass isolation became a reality, invalidating the differences between ideologies. The urinal and the hand washing sink appear to be hanging in the air, adding a whiff of supernaturalness and room for imagination to the picture. As far as Liu is concerned, the function of painting lies more in reflection and imagination than in gazing and perception. Implicit in the painting is a layer of invisible word-image structure. Whether the word-image split or word as image and versa visa, both point to the painting itself reflexively, which is also a manifestation of the “meta-painting” practice.

Anti-drawing—Institution

In early 2000 when Liu restarted painting, he decided to completely eliminate the legacy of fanaticism he developed during the 1980s-90s. While viewing paintings as an object for rational analysis, he also controlled his emotions as far as possible in the process of detailed description, in order to prevent personal emotions showing up in form or medium of the painting. Liu is not alone. Back in the 1980s, Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi applied the flat painting style and anti-drawing to their series conceptual paintings. Similarly, the flat painting adopted by Liu also falls under anti-drawing or conceptualization (idealization).

Liu’s painting practice most resembles conceptual art, as clearly evidenced by his selection of text as source material and the words in his paintings, not to mention traces of works, by conceptual artists like Sol LeWitt and On Kawara, found in the paintings. Conceptual art emerged as an avant-garde art movement during the 1960s and 1970s, featuring dematerialization, which originally related to the anti-commercial and anti-war movement. Artists then did not regard painting per se as the purpose even if they used the medium of painting. But for Liu, although concept forms a part of his language, his purpose is not dematerialization, and his final focus in still on drawing. Or we can even say he still considers himself a painter. Notwithstanding this, his paintings exhibit various anti-drawing intentions and characteristics. So, as part of the painting, anti-drawing points to the painting itself reflexively. In other words, anti-drawing painting is a kind of “meta-painting” as well.

That self-reflexive structure was earlier implied in Liu’s work Oil Painting Pigment (1993). With the realistic approach, the painting gave a partial view of a pigment box. Perhaps due to it coming from certain text, Liu applied the colors of black, white and gray. It is evident that the described object “pigment” also points to the painting per se reflexively. Similarly, as early as in the seventeenth century, Flemish painter Cornelius N. Gijsbrechts already incorporated painting tool or medium, as object or material, into his paintings. Stoichita considered it a way or path by which the painting resorts to itself or subjectification. Different from the painting where the repeatedly appearing palette may be believed to be a kind of paradoxical self-reference, another work Reverse Side of a Painting (1670-1675) shifted to an “ex nihilo” visual mechanism, where the paradoxical structure completely disappeared. Not showing the public a painting after reversing it, Gijsbrechts directly drew the real reverse side of the painting. Then, the reverse side of the painting itself became a painting, making the drawing per se the object the painter targeted. As a type of “meta-painting” practice, the negatory reversal or inversion reshaped the subject in a way that entirely desubjectized it.[10 Victor I. Stoichita, The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting, p.279.]10 Three hundred years later, American pop artist Roy Fox Lichtenstein also painted the reverse side of a painting. But for Lichtenstein, the reserve side already became a symbol, thus pointing to the painting itself in a clearer way.

Liu, though not as resolute as Gijsbrechts and Lichtenstein, used similar language logic in his “sizes” series works created in 2009. In paintings with different base colors, he wrote their size in bold of various colors, such as “68×120cm”, “80×110cm”and “90×150cm”. They represent both the size of the painting and the title of the artwork. Each size, just one word or concept, is at the same time the content in the picture and points to the painting itself reflexively. Liu has a clear understanding of such anti-drawing paintings, for example, what the size means to a painting. In the age of art capitalization, size is one important parameter used to measure the price of art. Liu refers to it as “independent art reality”[11 Self-narration by Liu Gangshun (in Chinese). Provided by artists, April 2020.]11, which depends on the genre, content or style of a picture, rather than factors outside it, like market and capital. This is perhaps the point this series of his works seeks to express or enquire into, explaining their similarity to practice of “new avant-garde” conceptual art or institutional art.

Gallery has become a component of modern art system since the twentieth century. As an organ of power, galleries seemed to sit at the top of the art emperor, building the art history and serving as the invisible conspirator of art capital. Chinese artists have always yearned for “holy places” in their mind, from MoMA and PS1 to The Guggenheim, dreaming of placing their own works or holding an exhibition there. Even having doubts about that, Liu did not portray how the Chinese artists longed for those “holy places”. In P.S.1 (2007) and Guggenheim Museum (2014), he textualized, symbolized and conceptualized the two places by describing their logo and building. His another work MoMA (2016) came out when he substituted “MoMA” for “Prada Marfa”, logo of the “Prada store” created by artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset in a town of the Texas desert in 2005. Admittedly, we can say art is both nature and commodity through the clever Dada-style replacement. But what Liu presents looks more like the unreachability of MoMA, and his true intention is not emphasizing the longing for it, but questioning such mindset. In this sense, “MoMA” in the desert appears to be a metaphor for China’s modern art system. It has no audience base, and is considered highly commercialized by outsiders, which in itself is a paradox. Of course, “MoMA” in Liu’s eyes, after all, is just a text, an ordinary container through which he collects and captures image motifs. But the self-reflexive mechanism in image is embodied not only in textuality but also in its (anti) institutional consciousness.

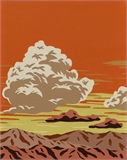

As far as Liu is concerned, “anti-institution” does not solely mean the entire art system. Painting (history) is in itself a stubborn institution. His practices primarily focus on the latter. His new work Cloud (2019) is a painting that features de-painting. The motif comes from the cover of the book The Cloud Collector's Handbook. In his painting, Liu removed the cedar in the foreground, highlighting the cloud and orange sky. He also deliberately created the visual printing-plate effect, so much so that the viewer would mistake it for a printed matter without a closer look. Same as the “sizes” series, the picture reminds us that although the work does not look like a painting, it actually is. The printing effect indicates the text source of the picture, and at the same time points to the painting itself reflexively. Painting is text, and vice versa. “There is nothing outside of the text,” said Jacques Derrida. Liu’s paintings are undoubtedly the most appropriate footnote to the famous saying.

Remarks: “Death of the Author”?

In Ashes (2010), Liu painted a scene featuring blue sky and white clouds, on which he wrote two red Chinese characters in large bold: Hui Jin (meaning ashes). “Under the blue sky with white clouds, turning into ashes is the ideal of a gentleman,” Liu said.[12 Self-narration by Liu Gangshun (in Chinese). Provided by artists, April 2020.]12 Here “gentleman” may be autosuggestion so that he can completely withdraw himself therefrom, or turn into ashes and void together with the picture. Perhaps, it hints precisely at the “Death of the Author” claimed by Roland Barthes. Barthes characterized text as a product of society, culture, economy, history, and so on, arguing the author only draws the text from these backgrounds. An author becomes the author only when text is created, existing neither before nor after the text. For this reason, the text itself does not contain any (added by the author) meaning except as a product knitted by language.[13 https://www.douban.com/note/573811302/.]13 Liu painstakingly simplifies his works to the greatest extent, and employs multiple language forms to avoid being classified into certain style or school — although we can still clearly identify his characteristics and orientations that are relatively apparent. The truth is Liu hopes to separate himself from painting as the thing he cares about is the composition of text and utterance. Although he does not refuse intervention from various explanations and even deliberately conveys some ambiguity and uncertainty, the purpose is not to add certain meaning from himself or reality. In his view, that is the original attribute of text, or “differance” or “reproduction” of text. In the words of Rosalind Krauss and Nicolas Bourriaud, it is “postproduction” that totally broke up “myth of originality”.

“Everything Turns into Dust”; “Everything Turns into Silence”. They are the names of two of Liu’s works. The first name is taken from the Tao Te Ching by ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi, and the second is a well-known proverb since ancient China. The first painting depicts a street view with green as the basic hue. In the middle is an image strip accounting for about one third of the painting, while the top and the bottom, each making up one third, are left blank. The middle image seems to be squeezed by the top and the bottom, and it also appears that the two blank areas are gradually engulfing the initially complete image. Maybe this is the true moral attached to “turning into dust”. The second painting has its background image derived from one work by American artist Alex Katz, and also conveys Liu’s imagination for the Beitang lakeside in Songzhuang art colony, Tongzhou district, Beijing. “Everything turns into silence. This is a constant truth,” he said.[14 Self-narration by Liu Gangshun (in Chinese). Provided by artists, April 2020.]14 The painting reveals a sense of void, from the background image to the foreground words, as indicated in his another work: “Everything is wrong.”

Void (2007) is based on the iconic photograph (Leap into the Void, 1960) of French artist Yves Klein. The release of the photograph marked the debut of performance art and a naive attempt by human toward the void. “… And this because the void has always been my constant preoccupation; and I hold that in the heart of the void as well as in the heart of man, fires are burning,” said Klein.[15 Quoted in Self-narration by Liu Gangshun (in Chinese). Provided by artists, April 2020.]15 Here Liu depicts not so much the performance photograph of Klein as a kind of void. Everything turns into the void. “Future is the ghost”. But it is bizarre that the void itself is the reality we are in. So calling Liu a nihilist may prove way too negative. While expressing the void, he did not forget to trace the spirituality and willpower reflected in “conciliarism”, “De Stijl” and Bauhaus. For him (and even all people), the real dilemma is not responding by creating a spiritual form to cope with and resist the void, but how to push such split to a level that is more extreme and thorough before finding a path for actions.