In 1979, Water-Sprinkling Festival-Extol Life, a mural painting by Chinese artist Yuan Yunsheng, was unveiled at the Beijing Capital International Airport. The well-known work proved to be a milestone in contemporary Chinese art, marking a beginning both for a new art form and for a social desire as symbol.

Twenty-seven meters long, the masterpiece occupies three walls at the airport. The painting was inspired by fables pertaining to Water-Sprinkling Festival, an annual celebration among the Dai ethnic group in Yunnan province, Southwest China. In it are figures of the same size as their real-life counterparts. Several of them are slender young girls portrayed with powerful lines. These lines serve two purposes. One lies in the full decorative effect in the existence of as few details as possible about how the figures look like. The other is about enhancing physical energy. Everyone is in a state of movement – life exists precisely in their movement and posture, rather than their face or eyes. It is movement that offers life internal power, immanence, which explains why life deserves praise.

Another highlight of the painting is several nude females. The scene makes life be itself again without social and culturali dentity. Apart from the removal of the cultural identity, to gain complete and fundamental absoluteness also requires an absolutely clean human body throug hall-round cleaning. And here is where the tradition of Water-Sprinkling comes in as a way to clean the contaminated body. Life is worth extolling not only because it is powerful, but also because of its cleanness. Life should fundamentally return to a pure body, one that is not polluted by any externality and transcendence, and that allows the power to spontaneously function inside. This represents an entirely fresh concept about life. Life nolonger continues for being devoted to some idea, nor should it be constrained by external transcendental power. Instead, what makes life meaningful and beautiful only comes from its pure, clean and absolute immanence. Only such life can bring freedom, as Yuan put it, “For me, the praise for the human body means the same for freedom.”

More importantly, the artwork carries historic significance by heralding a great revolution. Maybe we could regard the 1980s as an era when the “desire machine” started running. During the period, people began to take seriously their own body and their requirements for desire and beauty, trying to free them from being held back and fettered as in the past. Its debut at the airport especially made the fact a public and frank declaration infused with a widespread air of courage (as people even judged the historical landscape then by the fate of the mural painting). The huge collision with the past eratriggered tremendous volatility. Perhaps no other work in the history of contemporary art once provoked heated discussions as it did. The controversyended with dividing the history into two periods: one when life was controlled and constrained, followed by one when life engineered its desires after unlocking the past rope.

Yuan pioneered the trend of taking life as the subject matter, which continued through the avant-garde art movement emerging in China during the 1980s. Among all the themes involved in the vigorous artistic campaign, life was also in the spotlight. Afterwards, other canvases either boldly displayed various nude human bodies or expressed burning passion.

At the same time, however, Yuan led his understanding of and interest in life to another direction in the absence of human body. Following Water-Sprinkling Festival-Extol Life, he gave up the aesthetical and hygienic requirements for the human body that put its beauty and purity in the center of life. Yuan is also unique when compared with the later younger artists who painted the human body into a shouting thing in astate of imprisonment and depression, believing that life is recognized through such kind of intense cry. This is because for Yuan, life is not powers against external things, but the stage and theater for conflict between internal powers in itself, which forms his concept of life.

Yuan practiced that concept in the form of Chinese ink and wash, and created a large number of ink wash paintings featuring the style of expressionism. In his paintings, life can flow, driven by the powerful movement of the ink and wash. These artworks appeared amid agrave crisis for ink wash painting in the mid-1980s. The art form was interminal decline, as some critics claimed. They indeed had a good reason. The historical background supporting this kind of art had become a thing of past –whether as a lifestyle or an ideology, and whether as a natural structure or a social structure. The point is all styles and practices previously peculiar to ink wash painting cannot be justified without any foundation. Accordingly, if it was to experience rebirth, there must be transformation with new attempts.

How to transform ink and wash varied significantly and there were a wide variety of new attempts: Some employed radical experiments on ink and wash to declare it dead, by which the purpose was to make it get reborn. Some re-tapped into its dark side (exotic feelings) –long been restrained, adapting and pushing the obscure, marginal and profane ink and wash tradition to the front stage. And some others tried to introduce modern life or life in border areas as a way to reform the stereo typical system for ink and wash paintings. Whatever the means, all aimed to give ink and wash a rebirth. As for Yuan, the approach was to incorporate the modernism tradition of oil painting into ink and wash, or, more exactly, to use ink and wash in the style of abstract expressionism. In otherwords, he activated another side of ink and wash by perceiving the alignment between traditional ink wash paintings and modern paintings. Yuan said his belief is “When we review what modern art is pursuing after a thorough probe into ancient art, it will be likely that we can find a common basis, and realize that the pursuit of modern art is not such a far cry from what we are seeking in essence that necessary inspiration can be gained from it.” There is inherent rationality behind his combination. In doing so, Yuan is not transforming but activating ink and wash, to link the traditional form with modern art. Their connection seemed to be inevitable in the 1980s as ink and wash itself exhibits a natural affinity with expressionism that is pushed to the extreme, then to disorder and chaos, and ultimately to absolute abstractness – exactly what underpins traditional wild cursive calligraphy that has long existed in China. So the expressionism might not be totally different from the classical Chinese art. All said, Yuan connects them perhaps not for the sole purpose of revitalizing ink and wash. We can also interpret his intention in two ways: the invention of a new style of ink and wash, and also the search for a new form of painting centered on life. For him, flexible texture of ink and wash may be naturally connected to the feelings for flowing life. Emancipate ink and wash from the fixed pattern and let it move in a more natural way. Doesn’t this fit into the intrinsic reproduction of life with diversity?

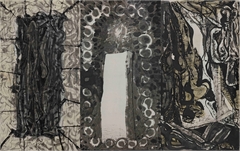

Yuan’s expressionism-style paintings in the late 1980s contained vigorous energy and power. The artist activated the mobility and penetrability ink and wash is born with. Without any control, modification and coding imposed, he let such energy and power play without restraint their role on the paper surface in a way that they can reproduce, rush and stretch towards all directions. So robust are they while pressing and hitting against each other that they seem to be ready to rush out of the painting and to the edge of the paper at any time. The result is a saturated yet messy picture, as if the drawing paper would stand ready to be broken by the brush at any time. All these paintings manifest only energy, but noinformation; they just display lines without fixing the image; and they are inconstant movement without a moment of tranquility. These jumping blind powerstear the human body into pieces. The fragmented body parts and organs then indistinctly crash, press, twine, push and fall in the painting. They decompose and recombineover and over again, going away from original location and functions before turning to new ones. In the process of making different kinds of attempts, the human body would lose stability, get rid of organic feelings, and eliminate the emotional, historical and cultural siege, returning to an inherent power. The lonely eyeballs, the severed hands, the fractured skull, the widely piercedbelly, the twisting face, the thighs without toes, the skeleton without the flesh, and the flesh without the skeleton – all body parts crowd the painting, colliding and recombining. We can not see the complete human body, but we seem to be able to hear it shouting and screaming, and hear the friction and roaring between one power and another. The human body is therefore disorganized, disturbed and destroyed by power entirely and thoroughly running through it. The human body comes as the stage and theater of power, a brutal theater without any center or rank.

The painting is full of curves varying in width, thickness and length, which “move” the painting. Some curves appear abruptly; some turn abruptly; some suddenly intersect others; and some suddenly vanish. These curves constitute both the rhyme and counter-rhyme of the painting. Highlighted in the painting, they maintain an independent style, so it seems that they are not forming the whole picture, but writing on their own. In this way, a sense of calligraphy is added to the painting. If we say that the painting is in a constant state of decomposition, another form of combination can also be noticed, that is the combination of atradition of wild cursive calligraphy and an abstract painting style. Simply put, calligraphy in painting, and vice versa. It is due to the lines spread all over the painting that the latter looks not rigid in rhyme, but the painting is not totally out of control, nor randomly interspersed with piles of disordered ink. Meanwhile, the unexpected, bending curves flood the painting with anoccasional, accidental and emotional impression, which is the very unpredictable trajectory of power, and the source of the intense volatility in the painting. Such volatility is embodied as the swing of lines, and also the volatility between strong and weak powers. In the absolute volatility of powers, what are hidden include beauty and ugliness, ideology and politics, interest and dispute, and history and reality. The only thing that remains is the confrontation between the strong and the weak, the competition between powers, and the breaking and stitching of the human body. That is possibly the pure life itself, the immanence of life, echoing the idea of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “It even seems that a singular life might do without any individuality, without any other concomitant that individualizes it... an immanent life that is power and even bliss.”

From Water-Sprinkling Festival-Extol Life to later abstract ink wash paintings, the focus of Yuan’s paintings remains unchanged: life. For him, life should always strive to find freedom from external control and return back to pure immanence. A difference exists between the two stages, though. The mural showed the immanent life still requiring cleanness and beauty in a way that brought about a historical situation; while in the following ink wash paintings, the immanent life, without the cleanness and beauty, only related to pure strength and power, which guided, through a herald, today’s diverse discussions about human body.