For Wu Shan, the disturbance of contemporary Chinese art that began in the mid-1980s has little to do with him. He graduated from Zhe Jiang Academy of Art in 1982, then he went to School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the next year. After graduation, he lived in USA for a long time. Therefore, he is a recluse for the Chinese art circle, a person who is close to disappearing. However, Wu Shan's artistic practice did not stop. Instead, he took a completely different path. While the most of Chinese artists were still "misreading" the outside world in low grade prints, he was immersed and meditated in front of the original masters’ artworks. While we were still arguing about the concepts of 'form' and 'abstraction', he has accepted to come into the systematic modernism education. However, when the native artists were afraid that they were not 'international' and 'contemporary' he has reached a winding path like kind of autochthonous spiritual tradition. It seems that Wu Shan's art is anachronistic, as Agamben said, Isn't contemporariness an anachronism?

Wu Shan started from modernism rather than vanguard art. Modernism was on a gradual decline at that time when he studied in the US, but Greenberg’s classic laws on modernism have already become a remarkable coordinate in terms of cognition, such as the emphasis on planarity and rectangular boundary. Such modern laws have turned into part of Wu Shan’s works, particularly his attention to laws, i.e., the methodology in itself. As a result, his paintings always remain clear and strict in visual form and logic. Comparatively speaking, systematic modernism is what contemporary art lacks during its development process in China, making the artists easily to come around thing-in-itself and indulge in the empty talk of concept.

Any concept without the support of thing-in-itself can only be an attitude-oriented standpoint. This is also true for the recognition about modernistic concept. What is thing-in-itself? Actually, modernism at large is constantly asking and trying to answer this question. Therefore, in addition to strict compliance, Wu Shan seeks to activate the recognition of sensibility about modernistic laws via personalized means. For example, the overlapping lines and shapes in his works often lead the audience to the subtle spatial illusion at the time of turning. But when we glance along these structures, the previous visual illusion diffuses in the entire shape formation. At this point, Wu Shan changed the established concept of planarity to empirical fact that needs to be grasped in feeling. In this sense, Wu Shan’s paintings boast the vigor and vitality of cubism.

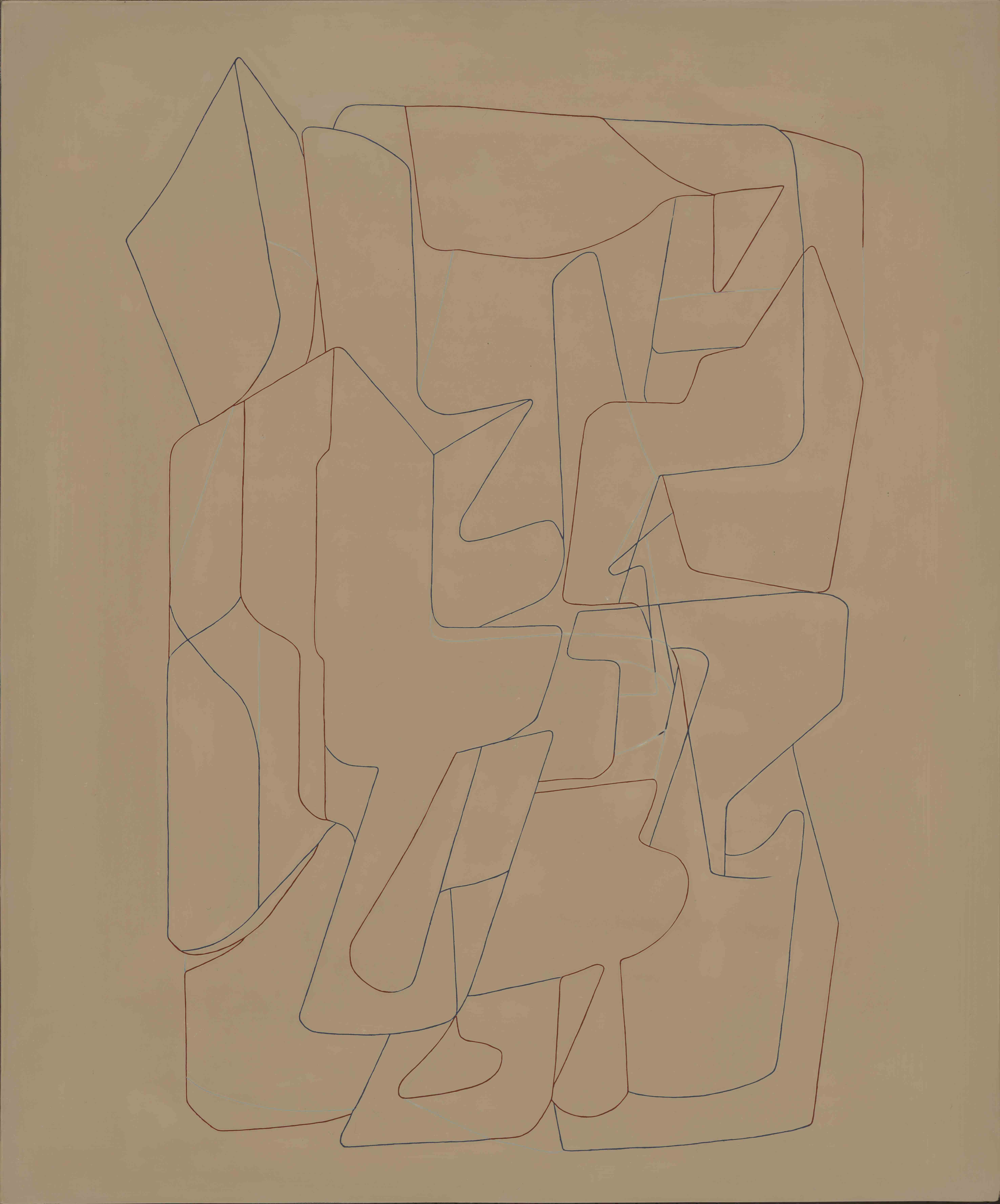

Indeed, his oil paintings produced in early days can demonstrate the trace of cubism as the relationship between color and shape is the visual logic he takes into account in the first place, while lines are often the boundaries among the shapes. But in his recent works, the value of lines is reflected in a more independent manner and becomes the most central language. These lines are close to line drawing in traditional Chinese fine arts which do not depict mould and objective image, but instead are constantly enclosed to shapes and then join to and form structures. Wu Shan’s lines have few sharp transitions, and also do not emphasize the representation of brushwork. It seems that the lines are at a constant speed permanently, point to the track of circular bead when turning away, and display moderation in all aspects. The paintings starting from lines also present a kind of linear growth logic and make up opportunity at all time. In particular, he does not set he final form in his line drawing on paper; rather, he begins with the possibility of structure initiated by any single line, gradually uses the mutually twisted and dependent shapes to overspread the center of the picture, and tentatively touches the blank part of the inner edge of the rectangular picture with the organic overall outline shaped finally.

This painting method of linear deduction is so much like the landscape painting method of Dong Qichang and four painters surnamed Wang in the Qing Dynasty (including Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui and Wang Yuanqi) who used lines to lead to block, and then stone and mountain. They only centered on the general “momentum” rather than an individual mountain and scenery. “Momentum” is people’s understanding about external order, and therefore means people’s intellectual ability. Here we can almost say “momentum” is pure beauty mentioned by Kant, is a kind of existence that goes beyond specific objective image and can be experienced by intellectuality. However, “momentum” also suggests indeterminacy and openness, and means the on-site status of perception. Therefore, scalability decision is necessary for every single brushstroke. If we say the emphasis on the aesthetic attribute distinguishes Wu Shan’s works from the ever zombified formalism, then methodological inference makes his works different from hollow oriental abstraction. To put it simply, Wu Shan’s works follow the intrinsic aesthetic tradition of China when running over the framework of modernism in the prime time. He does not regard “oriental feature” as a kind of signboard that tries to please the existing identity game.

Hence, even if Wu Shan brought into use lacquer, a kind of material with rich traditional flavor, he did not get into the common routine of oriental aesthetics. For his part, lacquer is, first of all, a kind of painting material featuring precision and stability, which coincides with his clear and strict style. Moreover, it is a skill which needs to consume time and process. As he produces his works, he must restrain his emotion further and express in a more indirect way so that he can get rid of contingency and solidify a purer form. Different from the lines in his line drawing on paper, the lines in his lacquer works are approximately embedded in the picture, and the weak comparison between the specially maintained natural color of lacquer and the color of lines often makes the lines indistinct. Therefore, the audience needs to get rather close to the picture to find the clue. Such way of processing has weakened vision, but highlighted physical property, and rendered to the works a kind of quietness like utensils which do not need external vision.

Art historian Jonathan Hay once described utensil decoration in China in early modern times (mainly the Ming and the Qing Dynasties) with Sensuous Surfaces. In fact, it is an over interpretation that translates Sensuous into 魅惑 as it refers to a kind of embodied perceptual intuition even more. In other words, Wu Shan selects lacquer squarely because of the vital cultural intuition as with his selection of the names of Kun Opera as the title of his works. Although we can’t say clearly the virtual or notional connection between his works and opera names, the characters such as Qing Jiang Yin, Tian Jing Sha and Yin Bu Chu can immediately arouse our visual prospect and aesthetic experience even though we are unfamiliar with Kun Opera at all.

In fact, Chinese artists who first came into contact with western modernism, eventually instinctively activated the cultural noumenon behind form and aesthetics. It was when Wu Shan studied in Zhe Jiang academy of art that he intuitively faced the problem of form and aesthetics through Hu Shanyu, Ma Yuru and Jin Yide. As a result, he is different from the arts that developed from the politics of the left-wing movement, whether it is considered in the maintenance of socialist literature and art system, or that avant-garde rebelling against the system, they all forgot the aesthetic/sensibility ,which is an effective way to connect art and human, but Wu Shan has not forgotten this, and he is maintaining its effectiveness though his works.