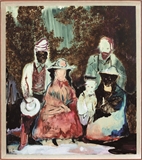

One

An oil on paper that measures less than one square meter unfolds before us. The painting is categorized as an ordinary family photo judging by the arrangement of the five figures (four adults and one child) on it. Their costume style comes as a reminder that the painting might find its origin from an old photo. The faces of three figures are painted white while those of the other two in black. Of course, what they wear is also likely to be a mask or even just pigment serving as the medium. Seen as a whole, the picture impresses us with a tone of dead color dominated by brown. Its spatial structure features distinctive layers in depth, including the front, middle and back. The artist adopts the techniques of expressionism or freehand brush work (a genre of traditional Chinese painting) while retaining the feature of realism by staying true to the basic structure and general mould of the characters. Furthermore, the picture is even blended with an element of romanticism prevailing across Europe in the 18th century. In other words, we are witness to a representational painting with a romantic style.

This is a new painting entitled Family.Q created by Chinese artist Fu Rao working and living in Dresden, Germany, in 2017. Although the painting highlights expressionism in terms of painting language and style, such expressionism is not pure German Neo-expressionism, nor the Abstract Expressionism originating from the US, and also differs from the expressionism which sprung up in Germany, Austria, France, Russia and countries in North Europe around the 1920s. Of course, from the standpoint of art history, the three forms of expressionism bear some kind of historical relevance rather than exist independently of each other from the very beginning.

Let’s turn back the clock to the 1920s when expressionism laid more emphasis on the manifestation of inner world, emotions and souls in lieu of description of the objective things to distance itself from impressionism and naturalism. Bergson’s intuitionism, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and Nietzsche’s ideas constituted the primary theoretical source of the creation of the expressionist school. Furthermore, a wave of expressionism emerged not only in painting, but also in all other fields including literature and film. The American Abstract Expressionism growing around the World War II was characterized by a combination of the abstract form and expressionism (including surrealism), in an effort to distinguish itself from School of Paris and further create art unique to the US. It is since then that New York replaced Paris as the world’s art hub. It is worth noting that art historian Michael Leja found out the same kind of perceptive mode shared by the film noir native to the US and Abstract Expressionism. The film noir per se was heavily influenced by the European expressionist films. Hence we are given insight into the blood ties between the American Abstract Expressionism and the European Expressionism in the 1920s from another perspective. Well into the 1970s, the expressionism gained traction with the German artists again amid their dissatisfaction with the American art, in particular the “shallowness” of the pop art, coupled with a deep reflection on the history especially the World War II and self-reflection, thus bringing the new wave of “Neo-expressionism”. Nevertheless, different from the expressionism in the 1920s and the American Abstract Expressionism, the Neo-expressionism no longer took its recourse to pure means and medium with a complete separation between painting and the reality. On the contrary, the Neo-expressionism had deep roots in history and real-world experience. Of course, Abstract Expressionism resorting to pure medium, plane or formalism could also be regarded as a kind of ideology in itself. Moreover, Abstract Expressionism and Neo-expressionism have long been “stuck” in history, and national and state identity. And therefore, the image hidden behind the stroke, color and form of Abstract Expressionism and its primitiveness was continuously unveiled, while it seemed all the more so in terms of the Neo-expressionism, which for the most part emerged as a representational expression, and was even called “figuration libre” in France. Finally, when coming to Fu Rao, his painting, not a direct result of certain specific expressionist school, seems to have, more or less, certain connections and similarities with each school.

Now, let’s refocus on the painting Family.Q. The picture, revealed the author, is actually sourced from a group photo of the family of Marx and Engels. Given the random selection of the picture, the artist gained inspiration from not so much a particular intent as the historical sense the picture is endowed with. It is just because of such sense of history that the picture holds special significance. The picture is left as a legacy from the 19th century, which witnessed the progress of industry, technology, culture and the society, the global influence of colonial powers along with the expanding capitalism, and also the birth of Marxism symbolized by the publication of The Communist Manifesto (1848), and later the publication of Das Kapital (1867). Needless to say, Marxism acted as the core ideological and institutional basis for the beginning of modern China against the backdrop of capitalism, colonialism and imperialism expansion. Admittedly, a historical narrative like this might sound too broad for us to appreciate the painting of an artist. However, it indeed provides a necessary background and path to allow us to dig deeper into Family.Q. For instance, different from the original image, two figures in the painting are presented with “black” face. What was his intention? The “black man” holding a hat in his hand on the far left of the painting looks more like a worker, with the background littered with bitumen. In my view, such technique is designed to create and convey a special visual effect to maintain the transparency of the medium. Meanwhile, the bitumen is in itself the embodiment of modern industry given the fact that the first road with the bitumen surface debuted in Hamburg, Prussia back in 1838. On the basis of the historical framework, we can view the bitumen as a hint about industrial progress, colonial movement and even a century, not just an element in the formation of the picture. But the question is, why did the artist choose to demonstrate the motif of the picture and its historical significance by means of expressionism, and further, how did the painting convey perceptions about the present and future?

In the eyes of Fu Rao, expressionism means subjective impression and summary, and is also likely to be a kind of conscious reaction brought by cultural estrangement. But at the same time, it is also a means to gain access to the inherent texture and spiritual foundation contained in his paintings. In this regard, expressionism not only pertains to aesthetic or style, but also, in its essence, is a path toward his concept or perception and reflection. However, the painting of Fu Rao is featured not by a single style, but by a combination of multiple techniques and means which are integrated into a whole in an organic way. Of particular note, in terms of quotation and reference from traditional Chinese landscape paintings, Fu Rao is strikingly different from other overseas Chinese painters who have always made great efforts into a blend of Chinese and western style. Take for example his painting Family.Q, although the overall structure of the picture conforms to that of the original photo, parts of the picture such as the hemline of the clothes worn by the two figures in the foreground of the painting, are somewhat infused with the taste of traditional Chinese landscape painting. This is because, on the one hand, the freehand brushwork adopted in the landscape painting shares common characteristics with the technique of expressionism in essence, on the other hand, the identifying mechanism behind the expressionism, the symbolism in the landscape painting, and their fusion and confluence are also embodied through the consciousness of his identity as an overseas Chinese artist. On this basis, regarding homesickness as an element of his painting is not that far-fetched. In fact, the painting Family.Q is not the only work of Fu Rao that contains the emotion of homesickness. For instance, a trail which winds its way deep in the woods and distant mountain is commonly seen in his series of works themed Dorfweg. Similarly, the Germans themselves live or exist with strong overtones of homesickness, as evidenced by the poems of Holderlin and philosophical writings of Heidegger. Heidegger’s Being and Time was first published in 1926. No matter whether the book had a direct bearing on the wave of expressionism over the same period, the proposition Heidegger emphasized that “existence precedes essence” still had something in common with the concept of intuition and subconsciousness advocated by the expressionists at the level of concept and perception. Furthermore, as the capital of the former East Germany, Dresden has long been known for being “rigid and conservative”.

Two

The figures in his painting come from either certain existing picture or a scene based on experience and memory, as repeatedly mentioned by the artist. The relationship among figures depends not on an established narrative or script, but on an accidental combination or continuous creation. Or put it another way, the painting itself is writing of stream-of-consciousness, a surreal fiction. Through his expression and transformation, these figures, divorced from those displayed in the original picture, can no longer be identified. Some become wizards, some look like monsters, and some others are merely a shadowy yet visible shape or symbol.

The narrative of Fu Rao always carries a kind of surreal mythological element, which can be seen not only through the portrait of figures, but also through their relations as designed or conceived by him and the whole picture structure. Despite the mixed relations and “mussy” structure, he seeks to build new symbolic relations through transformation instead of abandoning all the original metaphors. For example, the figure at the bottom left of the painting Legende (2017) is portrayed based on a Nazi officer during World War II but at the same time seems an imaginary clown, whose body facing the bottom left is fused with the pigment or medium. The right part of the painting shows three figures, including an old man at the most front who looks like a street beggar, and the other two ghost- or specter-like figures that would be almost invisible but for the general contours of their head and red “eyes”. Amazingly, the heads of the four figures precisely form a diagonal line in the painting, creating a feeling of movement from the upper right to the lower left corner. The background at the upper right corner looks like both tree shade and a cave, local part in the left of which is shaped like a pigeon scattered with some red strokes. What is fun is that these strokes echo or relate with the eyes or look of the aforesaid figures in terms of color. The same holds true for the background in the left of the picture, which looks like both a tree and a goshawk. Coincidentally and interestingly, the olecranon and the brim of the hat that the figure below wears correspond to or are parallel to each other. Such coincidence may provide a hint as to Nazi whose symbol is a goshawk spreading its wings. Apparently, the picture forms a dark and gloomy region or zone from the upper right corner to the lower left corner, which is a striking contract to the other two sides. Two purple oblique lines pass through the body of the goshawk and point to the eyes of the three figures and ghosts in the left, as if with a connection of two space-time existences. Between the dark zone and the white region in the lower right corner are two legs of a beggar-like figure. Similarly, the two purple lines correspond to the two legs ingeniously. It is thus evident that the painting of Fu Rao actually contains extremely reasonable visual logic and discourse structure which are embedded in complicated history and reality, even if his strokes, pigment and description means seem loose, natural and unconscious with even pursuit of an accidental effect of “unintentional good result”.

The latest Century series 2018 are distinguished from the previous works of Fu Rao by introduction of the features of the ancient landscape paintings into the primary parts of the former, even to a point that this form of the “Shen Yuan”(vertical view) landscape during the period of Five Dynasties (907-960) dominates the structure of the whole picture. An obvious mood of romanticism pervades the picture, but equally important is that the same mood can be found in majority of the extant landscape paintings during the period of Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Moreover, the tone itself also represents the materiality of history. In the paintings of this series, history constitutes the background of the picture or sets the mood for the main parts, with the specific traces seeming to become weaker and weaker, although we can still sometimes associate the image of certain local part with certain person or object in the past. Take for example the unidentified goshawk-shaped shadow hanging over the central part of the picture in Century 8. Although its relevance to the Nazi is not explicitly stated, there is at least no lack of correspondence between such image and the goshawk portrayed in the aforesaid Legende. It may also foreshadow a topic of war and history. The same subject can also be found in the painting Century 10. The skeletons are arranged in order in the left middle of the picture, which are naturally a symbol of death, while the central image of a giant who is pondering with his head down and a pole in his hand seems to be having a confession, but also looks like a wizard or specter pretending to be asleep. Nonetheless, the pigeon in the left offers a hint that the subject is also about history, war and peace.

Even so, the whole “Century” series seem to be more inclined to fabricate the relations among figures, objects and time-space. With regard to composition of the picture, the black zone in the middle of Century 8 seems like the section of a cave. The picture presents a scene where several persons are hiding in the cave. However, it is obvious that a few other persons in the bottom left have gone beyond the edge of the cave, which is designed to drive the imagination of the cave out of our mind by avoiding too much completeness of the cave. We could view such arrangement as the intertwining of two contrasting time-space existences. Furthermore, in many cases, the body of a figure in the picture melts into the scenery and the earth itself serves as a part of the human body (such as Follow Wind, Century 1, Century 7, Century 11). This seems to suggest a kind of “variation”, but is at the same time used as a reminder as to how we view the relationship between humans and the earth and humans and nature anew.

It is worth mentioning that the projecting geometric shapes spanning the picture are often found in the works of New Leipzig School in modern Germany. Perhaps Fu Rao has been inspired and influenced by the paintings of this school. Those geometric shapes in the paintings of Fu Rao seem like the collapsed buildings or ruins, and also the metaphors for science and intelligence, and calculation and measurement. An example is the patterns similar to the perspective structure in Century 2. Although these patterns appear out of tune with the picture, such “violent” intervention pulls the audience out of the narrative on the one hand, and on the other hand, the intervention itself helps create a new time-space -- of course, it is also likely to be a kind of abstract perception and understanding of the existing time and space. Similarly, the landscape paintings during the period of Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty are more than a manifestation of politics. Meanwhile, they also imply the principle of astronomy or astronomical phenomena. It is in itself a view of time-space or world, as the art historians have already pointed out. The scene where two persons, or specters, or ghosts leading a monster in the lower right corner of the picture reminds us again that this is a new time and space which is completely beyond our experience, an imaginary time and space that represents both the end of the world and the future. Needless to say, it is precisely the representational expressionism that effectively transmits the imaginary, fictitious, vague and mysterious meaning. This also helps explain the reason why artists have never been willing to abandon the feeling of depth and totally resort to sense of planarity.

THREE

As early as March 1869, the German geologist Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen who once coined the term “Sick Road” (Die Seidenstrasse) came to the Shandong province of China to conduct a three-month field reconnaissance and survey. In 1897, less than two weeks after the “Juye Incident” (two German Catholic missionaries were killed), the German Empire used the murders of the missionaries as a pretext to seize Jiaozhou Bay (formerly known as Jiao’ao) on Shandong’s southern coast. Shortly afterwards, the German ships landed at the Zhan Qiao pier (Tsingtao-Landing-Bridge) to attack the defenseless Chinese troops, and forced the Qing government to sign the Jiao’ao Lease Treaty. As a result, the newly established Jiao’ao (later known as Qingdao) was colonized by Germany. In 1914 when World War I broke out, Japan occupied Tsingtao in lieu of Germany until 1922 when it was taken back by the Beiyang Government.

Dresden in Eastern Europe is the second largest city in Germany, trailing only Berlin. Dresden used to be one of the most prosperous cities in the history of Europe. Unfortunately, the whole city was almost razed to the ground following the large-scale bombing from the allied forces including the US and Britain during World War II. However, over the several decades after the end of the World War II, people of the city managed to return the whole city to what it used to be step by step on the strength of unremitting efforts. Their outstanding achievement not only indicated national identity and historical sense, but also carried the spirit of self-reflection peculiar to this nation.

Fu Rao growing up in Qingdao went to Dresden alone in 2001 and has been studying, working and living there. He is attracted by the history and scenery of the city, and admires the German people for their reason and will as well. However, as an artist, Fu Rao is more interested by the close ties between the city with a long history and the popular art in Europe during the 20th century -- Dresden was a stronghold for the expressionism community Die Brücke (The Bridge) in early 20th century, and later the primary center for the Neo-expressionism movement. This is also the main reason why he made a resolute decision to work and live there after graduation. Even today, the history and scenery of Dresden are still a critical source of his painting material and style.

So far, three entirely different time-space and occurrence spread out before us. They seem to have no connection with each other, but as a matter of fact, certain hidden geographical and chronological clue connects the three into an integral whole, or we can say, fuses them together into the narrative of Fu Rao. Whether Qingdao and Germany in the history, the imperialist colonial movement in the 19th century and the two worlds wars during the 20th century, or Dresden and Qingdao in a globalized era, and even the recurrent romanticism in modern Europe and “imperial landscape” during the Northern Song Dynasty in ancient China in his paintings…These different time and space clues intertwine and together constitute the imagination of the artist for history, reality and future.

The end of the 19th century marked the beginning of modern world and modern China as China got involved into the capitalism-dominated world system amid the global colonial movement launched by the then Western powers. Historians have found out that the 19th century is not merely a concept of period, more important, it is an “independent and hard-to-name” era, just like such concepts as ancient times, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. For China, the thought of reform put forward in the 1890s can be regarded as a prelude to the next era as modern China witnessed a series of fundamental changes in the 20th century. Based on this, Professor Wang Hui also acknowledged the significant role of the 19th century, which symbolized a worldwide transformation, as the focus of historical narrative. To a certain degree, the two world wars, the Cold War and the advent of globalization that feature the 20th century can be traced back to the 19th century or the emergence of the so-called “century”. The end of the Cold War and globalization proved to be a catalyst for wars, trade, revolution, and technological progress, instead of terminating the latter. We can even say that it is just “century” that connects China to the West and even beyond, the whole world, or that China is integrated into the global system by “century”.

Fragmentary historical episodes in the 19th century and early 20th century in Europe tend to be the material and starting point of the paintings of Fu Rao. But he is not confined to the reproduction of the established pictures. Instead, he strives to, based on reproduction, create more complicated narratives accompanied by accidental introduction of personal experience. Such narratives are free from any preset clue and framework. In fact, without even a draft worked out in his mind for many times, Fu Rao is used to painting while thinking, and thinking while painting. His paintings are not lacking in metaphor and symbol of the ideology, including the consciousness of identity and anxiety of identification, but the overall logic of these paintings seems closer to aimless “stream-of-consciousness” or transcendental “time-travel drama”. As is said by Paul Virilio (French philosopher, urbanist and cultural theorist), it would never be possible for us to have a deep understanding of a variety of methods to perceive the world without “traversal”. I would rather view such traversal as a situation theory of action. The practice of the artist is not centered on the specific process of history evolution. The point is, with regard to whether the composition of the picture material or the combination of various expression means, almost every element and link is rooted in different historical and realistic situations, pointing to different political connotations. Upon a blend and recombination of all these, the artist creates a new, fictitious time-space or “century” scenario. Similarly, this surreal and allegoric “century” cannot be named either.

Perhaps only through this perspective and path can we be able to understand the perception and imagination of Fu Rao regarding history, reality and future world and the painting per se. Just Think. Why would a Chinese artist from Qingdao choose to go to and stay in Dresden? Why would he select the historical episodes during the 19th century and the World War II as the main source of his paintings? Why would he integrate the landscape paintings in ancient China, the romanticism of Germany, expressionism, and other elements into a whole? And why would he choose to create mythological narratives that feature the co-survival of humans, ghosts and mythical creatures, the co-existence of nature and violence, and the intertwining of evolution and last days? … For Fu Rao, the painting is like the future spiritualism. What he truly needs to do lies in how to pierce through all sorts of specters, layers of mysteries and potential unusual variants.