Wang Yin Interview ENG

Karen.Smith

2014.03

When did you first discover an interest in painting?

I started rather early; before I was even 10 years old. Then, in 1983, I came to Beijing to study at the

Central Academy of Drama in the department of Stage Design. In the 1980s, due to multiple new

trends that were unfolding, the cultural scene in Beijing was extremely lively, especially at the time

of the 1985 New Wave. During this time, I was also exposed to all kinds of Western art ideas, which

encouraged me to explore what were essentially experimental artworks.

Was there one trend to which you were particularly drawn?

I graduated in 1988. Just before that, between 1986 and 1987, I tried abstract painting, like

American Abstract Expressionism, which was an influence on many people at that time. I

also participated in a few exhibitions. In 1989, I was assigned a job in Xidan Cultural Workers

Art Troupe, so I was close by for the events leading up to the Tiananmen Incident. As a

young person, it naturally had an impact. After this, many people, me included, began to

have doubts about the kind of culture we had been embracing in the time leading up to those

events. In the face of turmoil, it all seemed so frivolous. In 1990, I moved out near the Old

Summer Palace, to the place that became known as the Yuanming Yuan Artists Village. There

were as yet few people living there. It was very quiet. I found a cheap house to use as a studio

and set my mind to work on creating a form of expression I thought could have meaning.

What was the general attitude towards painting in the 1980s?

For us, Western painting was hugely attractive. But the influences did not just come from

painting. Western literature, theatre, and music had equal appeal. At that age, it was natural

to be drawn to Western culture.

How were you taught painting at school?

My situation was slightly different from that of other students because my father was a

painter. In the 1950s, he studied at the high school affiliated with the Central Academy of Fine

Arts. I grew up around art. At university, I was also taught by my teachers who had studied

Soviet Socialist Realism in Moscow in the 1950s, so the influence of the Russian School was

strong. At the same time, the 1980s gave me an awareness of Western Modernism. Beginning

in the early 1990s, I drew on this knowledge, as a systematic analysis of all that I had learned,

to try to express myself in a more direct, credible fashion. This process was important to the

way that my painting subsequently developed.

This “systematic analysis” of what you had learned, was it in terms of technique or content?

It was focused on what I had studied and been exposed to; how those influences had come to

my attention, and the kind of impact they had on my personal view of art. These things were

of the greatest interest to me. For example, my study of the Russian School led me to consider

the relationship of this style to the social environment in which I existed. I was keenly aware

of this style in terms of its relation to myself. Why did I paint this way? Why had I chosen

to become a painter? This kind of question never occurred to me in the 1980s, but from the

early 1990s onwards, it was the prism through which I examined my work, as a means of

understanding what it was that I was doing.

You mentioned experimenting with abstraction in the 1980s, but looking at the language you

developed from the 1990s, you ultimately chose figurative art and, especially, figuration as a

means of exploring existing models in art history. What did this choice represent?

It sprang from my specific set of feelings towards art history and figurative art, and personal

interests, for example my research into painting of the Republican period (1912-49). This

research also began in the mid-1990s, and for similar reasons.

Was there a specific prompt for your interest in art of the Republican period?

When I was young and studying art, I looked at books, which gave me some knowledge

about this period, but by the 1980s, I had practically forgotten it all. In the 1990s, the

interest suddenly flourished again. In the early 1990s, some of my first works were on the

theme of Republic publications, particularly art publications of the times. I appropriated

that early style of Chinese oil painting, imitating the emotional timbre of Republican

period paintings together with topics from those times, in a style that was totally devoid

of contemporary essence.

In recent years, your approach to painting seems to be very precise. Although your works

still reference art history, your style has become recognisably your own. Would you say it is

contemporary now?

In the 1990s, by comparison with the prevailing aesthetics of the times, my paintings

were distinctly old-fashioned. Yet, I felt they were appropriate to the times. I consciously

pursued this style. Looking back, I can see that it wasn’t only in the 1990s that I began to

have my doubts about Western cultural influences; it was there in the 1980s, too. I realised

I was questioning the mechanism by which I received those influences. It was like I was overwhelmed by too much information. Those new things began to lose their appeal.

So it’s correct that your style became fixed fairly early on? Or are you still searching?

In the early 1990s in the artists’ village, I produced a series of paintings inspired by the

literary magazine Fiction Monthly (a popular publication from the 1980s). Since then, my way

of working has not changed greatly, neither in subject nor style. I realised I wasn’t interested

in unfamiliar subject matter or approaches to painting. After 2000, I discovered a particular

interest in taking on subjects that other artists frequently tackled in art history. One example

is the recent series on the theme of Minority Peoples. This has been a hugely popular topic in

modern Chinese culture and painting, so it appealed to me. This is the same for portraiture,

figure painting, which almost mundane as art today and yet artists always return to them.

That phenomenon interests me too. Why do artists keep painting these subjects? What is the

relationship between their works and my own?

In tackling these familiar topics are you trying to find a new angle or perspective?

I am keen to see if I can find a different aspect to them. You could say I am drawn to search

out the unfamiliar in the familiar.

Who are your main influences?

It is hard to say. There are many artists I like. Or, different ones I looked to at different times

in my life. I can’t say that there’s one artist in whom I have an enduring interest, but I am in

awe of an artist like Cezanne and remain fascinated about the process of his painting.

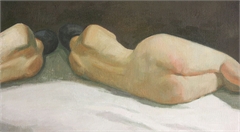

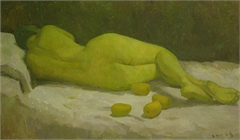

One painting in particular — the elongated figure of a female nude shown from the back —

seems to reference Cezanne’s style. Is this intentional?

Yes. When I made this painting I was revisiting the kind of thinking that inspired me to

make paintings in the 1980s when I was exploring Western styles of figuration. This painting

represents the ideas used to understand figuration in the mid-1980s.

What is the impulse for the recent use of motifs that relate to Japanese culture?

There is an overlap here with the idea behind the paintings of Minority Peoples, an element

of the exotic they suggest. At the same time, much about modern painting came to China via

Japan. But more importantly, I like painting these motifs and Japanese-style forms. I don’t

want to analyse that impulse too much.

Do your paintings contain narratives?

Sometimes there are stories. But to say that, or to look for the story, is also a kind of red

herring. There is a deliberate ambiguity there.

Do you have an idea of what a painting will look like before you begin? Is there room for a

painting to evolve in a completely different direction in the course of painting it?

Both can occur. There is always a difference between what you envisage at the start and the

result you end up with. That’s natural. It has nothing to do with the artist’s ability to control

the process.

Within your paintings you often repeat the same composition or elements with only very

subtle differences to distinguish them. Why is that?

I think most painters return to motifs or compositional forms. It’s natural. From traditional

Chinese painters to Western artists like Van Gogh, artists repeatedly paint the same person,

the same pose, the same scene again and again. Often the impulse is one of your own

paintings. That’s very natural.

So it has nothing to do with making the painting better, with getting it right?

No. It is like the painting didn’t go far enough, or hadn’t reached its full potential. To make a

painting requires a reason. I often find that reason in revisiting a theme. There is nothing that

demands greater attention than those paintings and themes already in hand.

Conventional thinking says that when artists revisit themes in painting, the goal is to capture

an emotional nuance, an atmospheric or psychological timbre through the paint. This is

understood as an artist pushing the material to achieve the language they desire. In China

most painters are trained to a high degree of technical proficiency and are not necessarily in

need to find their own means to resolving an issue of language through paint: they know too

well how to achieve the desired effect. Is painting easy for you?

I believe oil painting to be a foreign import. I feel this very strongly. Although I fully respect

the fact that I can deploy oil paint to reflect my ideas with a fair degree of accuracy, but I am at

the same time aware that the oil painting is not native to China and does not come naturally

to us. This awareness is also underscores the work I do with painting.

How do you decide then if a work has reached a successful conclusion?

Sometimes, I think my judgment is not necessarily definitive. I decide a work is interesting, is

done, but six months later I may decide otherwise. This is a frequent occurrence.

The process of creating a painting in the studio is an intimate one. How is that intimacy altered

for you when a painting is displayed in public?

There are times when I see my work in a public venue and I feel as if I am looking at someone

else’s art. I often have that sensation.

How do you understand the “contemporary” in art today?

Contemporary feeling is beyond all those things that are already “known”.

The prompt for About Painting was the oft repeated statement that painting is dead, or dying,

yet remains ever popular. As a painter, what’s your view on this?

I can see how people might think this way. There is no problem with the logic behind that

idea. The problem is more with the line of reasoning brought to forming this conclusion: the

fact that people still perceive progress as being a single straight line forward. So it’s not the

conclusion that’s at fault, but the process by which it is reached.

What is the power of painting in your view?

It never occurred to me to think of painting as powerful, or equally to think of it as powerless.

I do not think of painting in such terms.