Strange Guest is the title of a 2015 painting by Tang Dayao. The painting depicts an everyday scene from his past experience: one day, while visiting his family home in Hunan Province, he saw a man in a tattered shirt standing at the gate, looking around. The family dog barked and ran at the man, and the artist’s brother unconsciously ran out to scold the dog. This exceedingly ordinary scene awakened a certain childhood memory for the artist. He remembered that when he was young, his home was always quiet. He yearned for activity, and hoped a guest would come. Later, when he went to Guangzhou for university, he gradually grew accustomed to the solitary life. The image of the painting is fixed in this moment. As Walter Benjamin said, “For authentic memories, it is far less important that the investigator report on them than that he mark, quite precisely, the site where he gained possession of them.” Tang Dayao’s goal is to attempt to bring this “strange” mental state and experiential perception into his painting practice and his thoughts about painting itself.

Knowledge and life form the two experiential foundations for Tang Dayao’s painting. Here, “strange” denotes both distance from experience and ambiguity in knowledge. In theory, alienation is one of the core principles of Russian formalism, its essence lying in releasing people from the narrow confines of everyday relations so that they can cast off conventional constraints and mechanical models and thus renew our dusty perceptions about people, things and the world through creative discourse. Of course, formalism is not the reason Tang Dayao drew from this concept. His understanding of “strange” is more of a specific sense. In this painting, he uses two-dimensional methods to compress the depth of the image, and uses surrealist techniques to draw the narrative to another realm of the imagination—cancelling out all recognizable elements of people and things to generalize or abstract it into a conceptual human-object relationship. I see this as the interval within the image itself, as well as an ambiguity in recognition bestowed on the viewer’s gaze by the painting. It is a “spatiotemporal form of perception” that cannot be objectified.

Tang Dayao does not shy from the fact that his earlier creations were inspired, in terms of composition, form, brushwork and color tones, by such European contemporary painters as Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans, but Tang’s work also clearly shows a strong classical foundation. Around the year 2007, he painted a dozen profile portraits in the Renaissance style. At the same time, we can also clearly see traces of his academic training rooted in the Soviet realism model, with the artist even treating the block outlines meant to give substance to shapes as shapes themselves. For instance, in the 2013 Peacock, the depiction of the artist lying down in Untitled and the head in Incident, the necessary and superfluous modelling techniques constitute the end goal and result. Unlike most people, who, facing these background resources, either methodically follow convention or start afresh, Tang Dayao seems to be enamored of these “old” modelling techniques, finding joy and the potential for change within. The greatest potential for change comes from Richter. Before this point, Richter was already the focus of much discussion and reflection in Chinese contemporary painting, but this did not impede Tang’s passion and interest. To this day, his brushwork still retains certain characteristics of Richter’s painting. Later, Tuymans’ influence led him to loosen his paintings, while the color tone became heavier and more melancholy—which in turn blurred the expressions of the figures within. At this time, Tang removed the strong color contrasts of classical painting that marked his earlier works, plunging his paintings into an overarching gray tone that speaks to unclear circumstances and narratives.

Richter and Tuymans burst into Tang Dayao’s painted world like “strange guest.” If the paintings of Richter and Tuymans touch and reflect on history, war and memory, then what Tang Dayao’s painting touches are individual memories and life experiences. The connections and structures of the blocks formed with large brushstrokes define the overall precision and sense of mass in the painting, while the erasure of much of the recognizable information seems to bestow the people and things in the paintings with a sense of ritual and symbolism. There also appears to be a tightly wound tension between plane and three-dimensional shape—though it is often concealed by the melancholy atmosphere and expressiveness of the painting. It was in this process that Tang Dayao gradually came to realize the limitations of Richter, Tuymans and other European contemporary painters, which led him to turn back to Paul Cézanne, Edouard Manet, Gustave Courbet and even Diego Velazquez.

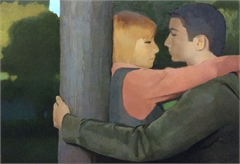

This is not to say that art history or knowledge forms the starting point of Tang Dayao’s painting. He also trusts and relies on intuition, experience and perception. Thus, virtually all of his motifs stem from his life and memory. He draws from the photography, film and internet technology that dominate our visual discourse and narrative methods, except that in the act of depiction, he also incorporates certain “little known” techniques and approaches from the history of painting. In his works from the past two years, the images are generalized and simplified as in the past, but the visual structures, formal relationships and layers of brushwork and color have become richer and more vivid. In other words, he has created imaginative, alien visual results from the mutual interference between knowledge, life and other forms of experience. The basis for Embrace (2014) was an image taken from the internet. The artist’s selection was not based on any particular thinking or supposition on behalf of the artist, but was entirely random and serendipitous. During the painting process, however, he discovered that the boy’s intruding, powerful arm resembled the out-of-proportion arms in Cézanne’s Card Players (ca. 1895), while the brown tablecloth in Cézanne’s painting corresponds to the color of the girl’s top in Embrace. This naturally led him to reference certain techniques of Cézanne’s, particularly in the arrangement of brushstrokes and general modelling. This referencing was only limited to certain details. In the overall painting, Tang Dayao was driven by a relatively classical, solid and stable visual structure, rather than Cézanne’s painting, which is controlled by dynamic observation and its temporal dimension. If it weren’t for that hint of blue sky at upper left, then the composition and modelling, including the ambiguous lighting, would seem to be describing a flattened formal construct. It must be noted here that the punctum, which is easily overlooked, actually stems from Manet’s Music in the Tuileries, in which a naked patch of sky is also visible. This implies that even though the overall painting is the result of a flat, fixed view, the artist’s intentional compression or closure of the depth enacts a transformation from vision to object. That is to say, he is attempting to depict a thing rather than reveal a certain motion or time.

At Noon, created in the same year, depicts a scene of two farmers capturing snakes. The base image also comes from the internet. Applying the compositional analysis method for ancient Chinese shanshui landscape painting, the image is divided into a foreground, middle distance and remote distance. The overall image has a green tone, with the green of the middle distance occupying most of the painting. The foreground scene consists of the farmers and the tools they are using to capture the snakes. The remote distance reveals a strip of deep green. The composition lends the painting a sense of stability. The entire painting appears shrouded in the light green of the middle distance, while in the modelling process, the artist intentionally generalized and refined the specific objects in the base image, resulting in a flat plane composed of green blocks of varying size. The trees, people, farming tools and snakes in the foreground are all nearly parallel, which is naturally intentional on part of the artist, the goal being to cover the middle distance with a flat layer. It is worth noting here that the person on the right is not standing straight, but is facing away from the viewer in a running stance. This detail doubtlessly breaks the flatness of the painting, and, together with the uncovered section in the middle distance, releases a structure of depth and a propensity for motion. In the end, painting is the tearing of spatial coordinates to open up different formal spaces.

Tang Dayao does not shy from discussing the inspiration he has drawn from Manet. The window shutters in Balcony, the gate posts in Railway, the bench in Madame Manet in the Greenhouse, and the texture of the clothing in Argenteuil are all parallel planes in a state of tension with the depth structure of the image. Of course, there are profound social motives behind Manet’s practice, which Jonathan Crary summarizes as awareness and reflection on the modern social order. Following this interpretation, we can say that Tang Dayao also harbors many similar feelings. This is an experiment rooted entirely in living experience. He may not have considered such a sweeping theme as modern society, but he has at least witnesses the changes that urbanization have wrought on his hometown. The mentality of Strange Guest is rooted in this social change. It not only references the formation of the external modern order, but also incorporates the inner, moral world into a new order. This also implies the disintegration and collapse of the old moral order. As the artist said, he found after many years that he no longer belonged to the countryside, but nor did he belong to the city. Wherever he goes, he is a strange guest. Here, he has extracted the graphic narrative, setting it aside in favor of visual discourse. In fact, those lines extracted from the painting are a mental state filled with contradiction, though in my eyes, perhaps X.W. better embodies this awareness, perception and possible reflection.

The two paintings titled Xiao Wu are based on the same image motif, a frame from Jia Zhangke’s film Pickpocket. The basic composition and modelling of the two paintings are the same, with the difference being that in the second painting, the window box has been flattened and the bed has been clearly raised above its position in the first painting. Now that the viewer’s line of sight has been raised, the angle of the figure has been reduced, making the figure’s legs appear thinner, thus enhancing the contrast with the rest of the body. This shift in modelling has its roots in Velazquez’s Portrait of Sebastian de Morra. According to Tang Dayao, the resemblance is coincidental, but aside from formal resemblance, what truly interests the artist is the resemblance in meaning and character. To many, a social figure such as the pickpocket Xiao Wu is little different from a dwarf. The artist has revealed this social (moral) property, while also, like Velazquez, granted his subject dignity. Having grown up in a rural area, Tang naturally has a deeper understanding of a character such as Xiao Wu, perhaps a bit of empathy. Xiao Wu is of course a product of the modern social order, but at the same time, he is noise within this order, forming a destructive force against it. Thus, when employing art history resources, Tang Dayao was not only concerned with image and form, but also considered possible connections on the level of meaning and recognition, thinking about how to draw from knowledge experience to bring new understandings out of memory and life experience. This understanding may be murky, but it is real.

It seems to be a habit of Tang’s to either focus on the backside, remove facial expressions or simplify the entire face into an abstract plane or block. Because of this, we rarely see a gaze coming from his paintings, but many of the actions of his figures suggest viewing or gazing. For instance, Tang did not depict the face of the man in looking back, but we can still “see” a pair of eyes gazing out from the painting. Of course, the thinking behind Tang Dayao’s “design” of the gaze is not that simple. In such works as Untitled (Back of a Person), Snooping and Sketch, he leads the gaze into complex spatial relationships, while also reminding us that this gaze conceals his complex mental state and concepts of painting.

In Untitled (Back of a Person), Tang Dayao draws from Manet’s use of external light in The Fifer, while also cancelling out distinctions between light and shadow, highlighting the basic outlines and flatness. He also references certain painting techniques from folk art. By not limiting himself to standards of modelling, he makes the figure more vivid and interesting. One can imagine the external light washing out the figure’s distinguishable traits. Thus, it is not that there is no gaze, but that the gaze has been swallowed by the piercing external light. Spy, on the other hand, contains multiple gazes. Aside from the gaze of the spy in the painting, there is also the photography. We are spying on the gaze of the spy. Then there is the spying gaze of the artist, and the viewer’s gaze at the painting. None of these “spying” gazes, however, is visible. Tang Dayao has told me that the spy in the painting is actually himself. This self-referencing is doubtless a psychological allusion. Indeed, Tang Dayao often shies away from directly facing changes in the real world, but he can hide in a corner and secretly take it in. He must maintain a “safe” distance from reality, at least to prevent others from seeing through or intruding upon him. Just like Georges Seurat, he always makes his people and things so solid, always bestows them with some crux of stability, and remains silent throughout. In the words of Georges Didi-Huberman, the mass or form here may be a body, but what it reveals is the loss, destruction or death of another body or object.

In terms of complexity, Sketch far surpasses Snooping and Untitled (Back of a Person). Tang has devised many junctures within. The painting depicts a life study in progress. He intentionally enlarged the body model, while shrinking the painters to create a stark contrast. The layout of space between the shape behind the sofa, the model’s form and the three painters forms a parallel, staggered depth. Interestingly, the painters have been replaced by puppet-like black shadows. That is to say, the painting is being done by shadows rather than people. The shadows of the shadows are themselves a metaphor for painting, as painting originated from shadows. The shadows have no gaze—the gaze is beyond the painting. Thus, the painting shadows are painting itself, or the fact of painting. As the controller of the painting, the model dominates not the shadows but the gaze beyond the painting. The painting shadows are just cross-sections, translucent screens. At this moment, if the shadows in the painting are depictions of the body or objects, then Tang Dayao, himself outside of the painting, is depicting painting itself. Furthermore, we cannot rule out that the model is also a painting. In this way, this so called “life study” has become a concept, rather than a fact. This demonstrates that a painting, no matter what is painted, first and foremost depicts painting itself. This is a painting about painting, a painting full of self-referencing and examination.

In the 1970s, the self-referencing and self-examination of painting began an external shift. This is connected, to a certain extent, to Michel Foucault’s lectures on Manet in Tunis. To be precise, Foucault led thinking on painting towards a system. Today, it is not rare to see contemporary painters employing knowledge of the history of painting to respond to the changes taking place in society and culture in their time. Tang Dayao appears to be strictly abiding to the two-dimensional plane, but his experiments (including recollecting and referencing painting history and his reflective references to reality and self) have transcended the painted plane. Of course, it is not just the form and style of his paintings that lead us to believe he is adhering to a classical form of caution and control; it is also because all of his paintings seem to have nothing to do with the art system (the market, commerce, capital, etc.). The acceptance of this system has become a basic condition for his experiments. In this way, he maintains a distance and sense of unfamiliarity from everything from painting itself to the world in which he lives. Just like “self-referencing” and “self-examination,” it cannot be clearly defined, nor can it be refined into a set of methods and models. Tang Dayao himself is not entirely clear about the issue he is facing. But the return to painting history and deep awareness of self-experience have indeed turned it into a mechanism of subjectivity and potential energy in his painting. Thus, the so called “strange guest” is at once a gaze and a way of thinking, and even more so a state of cognition. As Jean Baudrillard said, painting has never been a mechanical reaction affirming or negating the state of the world. It is a deeper illusion, a double curved mirror. In a world that strives to be cold, all it can do is add to this coldness, and this coldness itself has come to form a sort of “intrusion” (including towards the self).